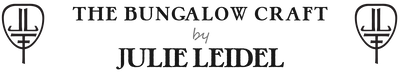

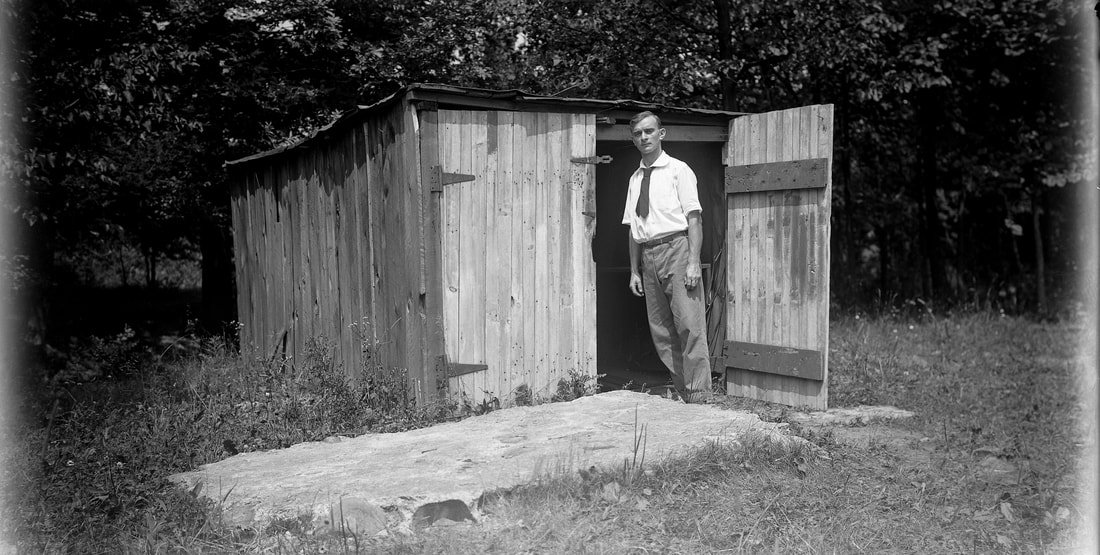

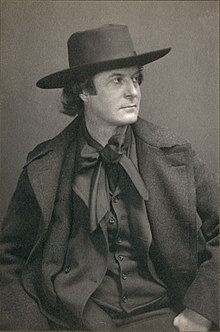

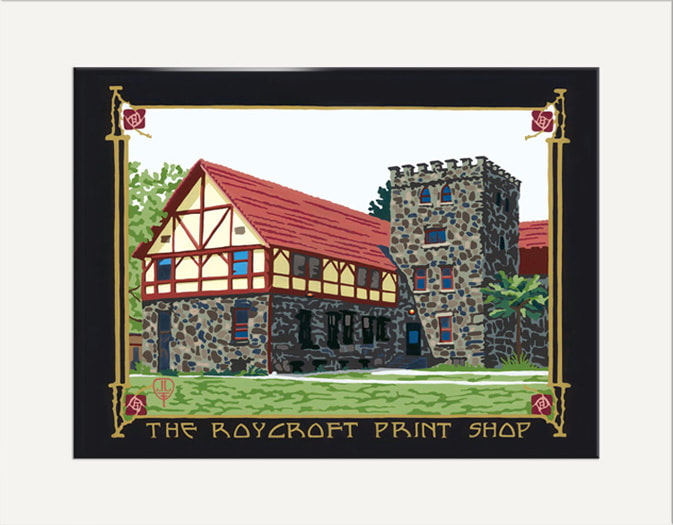

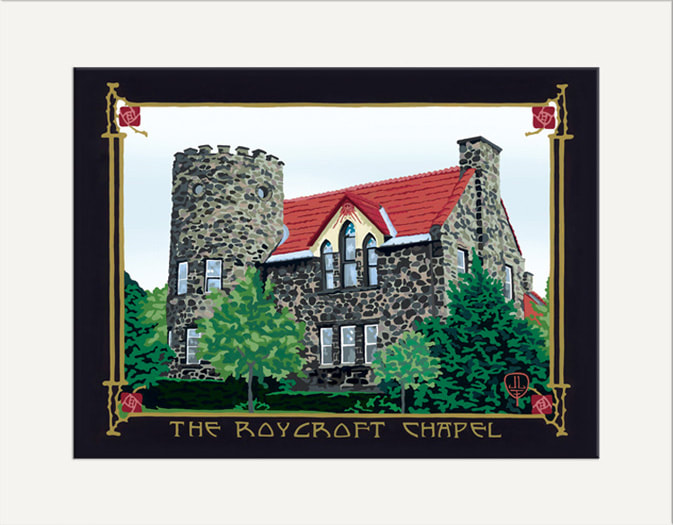

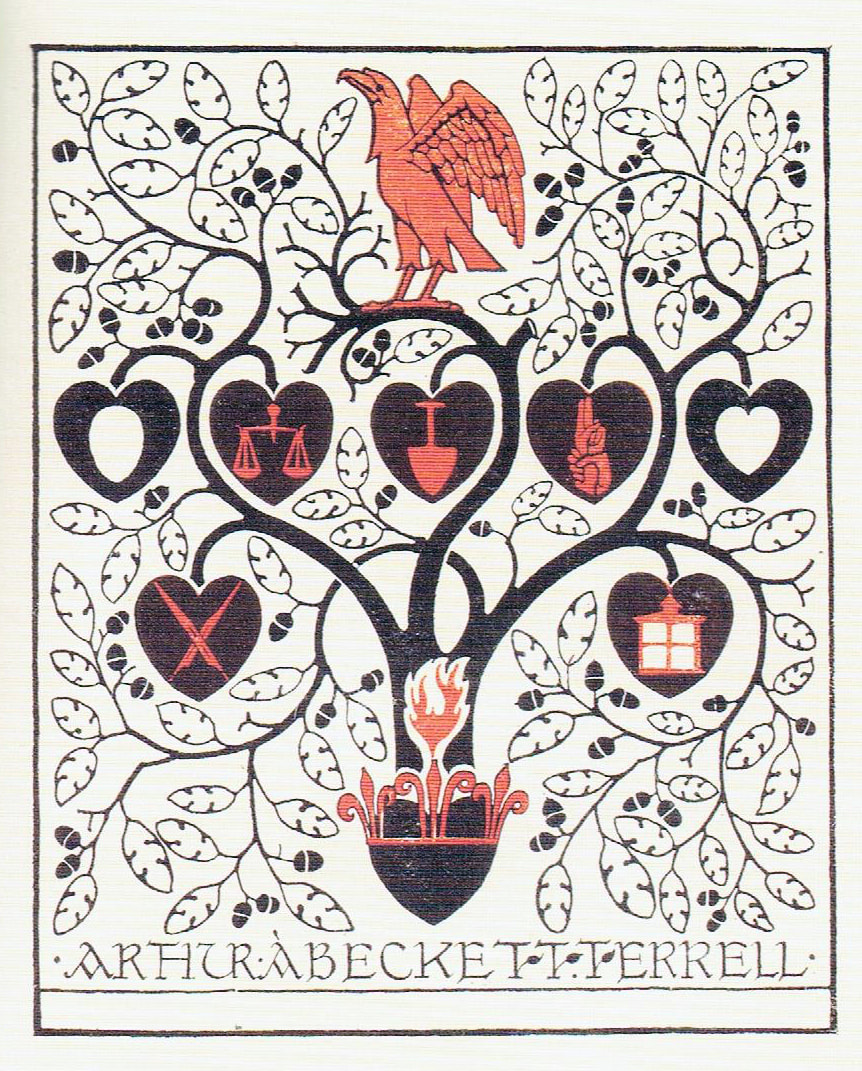

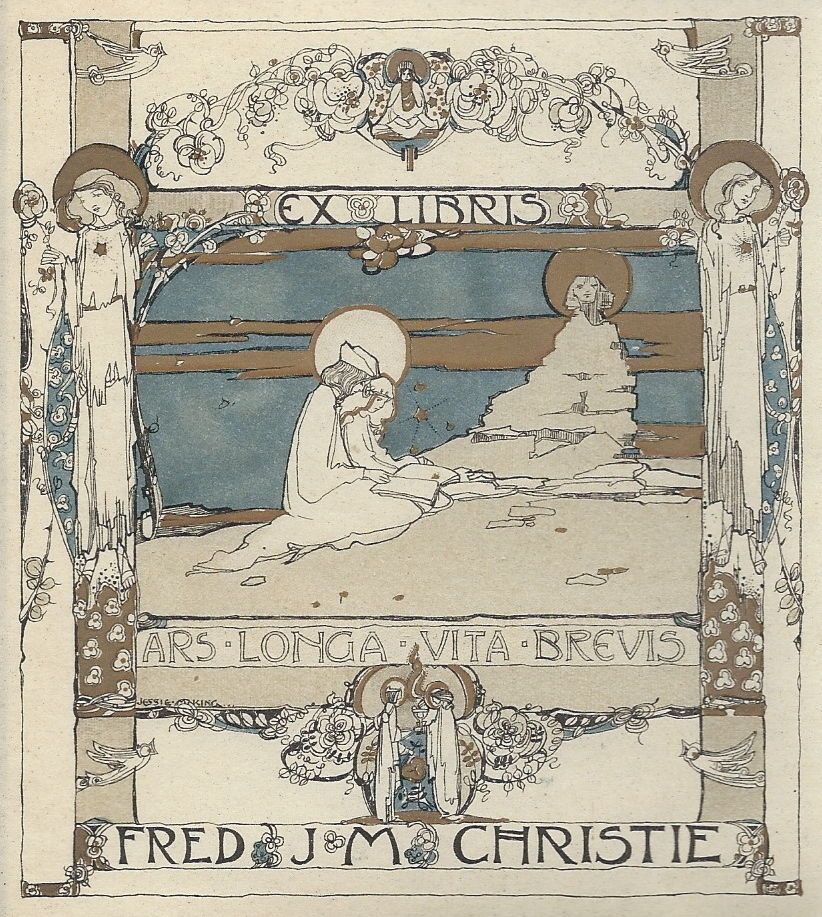

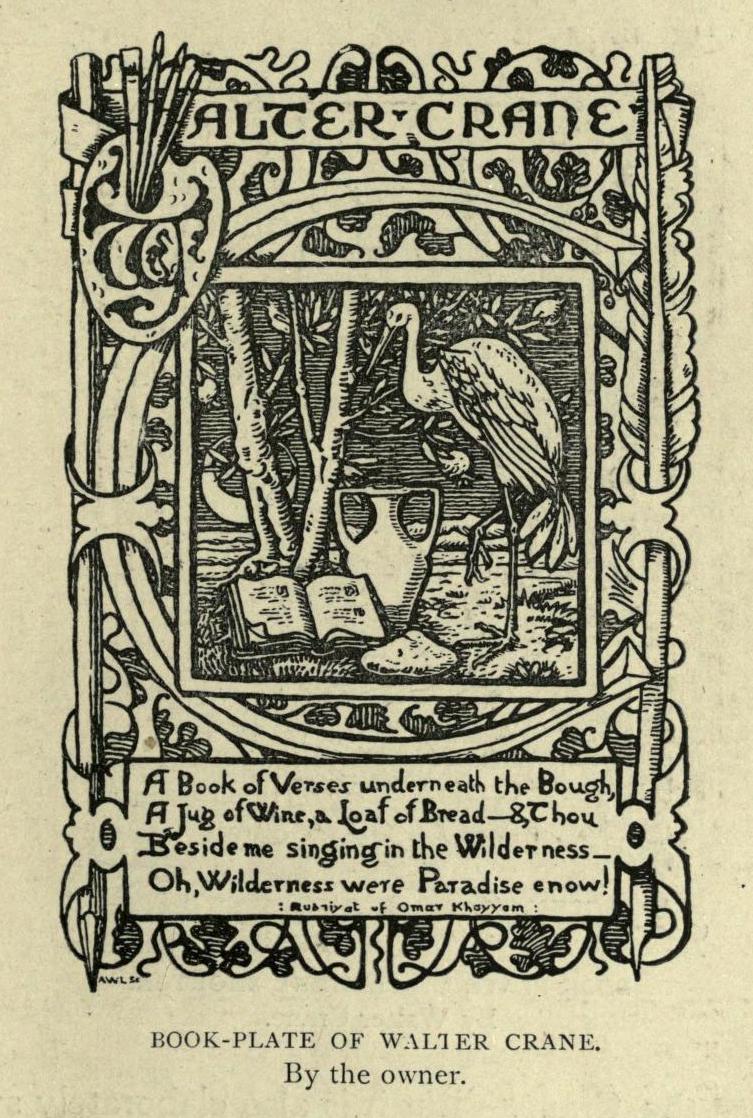

| A Documented Life: Connecting the Past to Present through the photographs of a Roycrofter - by Drew Jensen My great-grandfather, Terence Denz, lived his entire life in East Aurora, NY. Born in 1891, he was raised with his brother and two sisters on the outskirts of town. In a time when farm labor was the most common way to earn a living in rural America, the Roycrofters afforded him a rare opportunity to work in a new industry with the rise of the Roycroft Print Shop. The son of a contract painter, he understood a hard day’s work and what it provided. Sometime between 1906-1910, he began working at the Roycroft Print Shop, and by 1910, he had earned himself a position as a Pressman. He continued his work there until March of 1918 when he enlisted in WWI. After nearly a year overseas, he returned from Brest, France, in February 1919. Upon his arrival home, his skills, hard work, and reliability earned him a letter from the Roycroft requesting his return to work as a Pressman in the Print Shop. There he would work for nearly 20 years, until the close of the Print Shop in 1938 when the Roycrofters filed for bankruptcy. And though the details aren’t clear, when Samuel Guard purchased the Roycroft Campus, he reopened it with the help of former shop workers. My great-grandfather was one of those workers, continuing his tenure at the Print Shop until 1941 when Sam Guard, too, filed for bankruptcy, closing the shop for good. My great-grandfather didn’t take his skills to another print shop after the close of the Roycroft. As far as I know, he never used his lifetime of printing skills and knowledge again. He closed that chapter in his life and moved on. By the beginning of 1942, he was employed at Bell Aircraft as an assemblyman, helping prepare the US for another World War. A World War that, at the spry age of 50, he honorably enlisted in. My great-grandfather passed away in 1968 at the age of 77. Through the personal effects he left behind and the stories told by his children and grandchildren, I never got the impression that, beyond providing for his family, he thought his work would hold any value after he was gone, let alone leave a legacy. A legacy his great-grandson would strive to uphold 50 years after his passing. Having digitized my film negatives in college, I was tasked by my family with scanning and protecting these glass plates. A process that would profoundly impact the direction of my life, ultimately leading to the pursuit of a dream I never thought was possible. My great-grandfather’s life is an inspiration to me. His skills as a Pressman were appreciated and valued, and his longevity at the Roycroft Print Shop was admirable. In truth, I probably have a romanticized view of the man, at least when it comes to him as a Roycroft Artisan. He was a Roycrofter, and his skill set was a greatly valued asset to the Roycroft Print Shop. I have gleaned from his personal effects that his career at the Print Shop was dictated more by the circumstances of the time than an internal drive to be a part of something revolutionary or creative. I would consider him a skilled and knowledgeable tradesman by modern standards. The Roycroft uniquely positioned itself with a foundation based on the Arts and Crafts values of hand-crafted and the use of modern technology to share its work with the world. It’s easy to forget today that the Roycroft Print Shop was a modern outfit at the time, requiring skilled labor to function—the skilled work of its Roycrofters. Although his work in the Print Shop was the driving force behind my infatuation with my great-grandfather, the most inspiring thing didn’t come from his work there. It came from the glass negatives we found of his family, his town, and his place of work. The documentation of the people, places, and things he valued enough to capture on his bulky 4x5 field camera, his documented life. In 2022 I fulfilled an aspiration of mine to become a Roycrofter like my great-grandfather. To earn the distinction of Roycroft Artisan and the right to adorn my photographic work with the “RR.” To carry on the legacy my great-grandfather left me. To document the world around me as a Roycrofter, with HEAD, HEART, and HAND. The images shown throughout this article, taken by my great-grandfather, are the inspiration for the direction I intend to take my photographic work in the coming years. Shifting back to analog photography, the version of this medium that I fell in love with nearly 20 years ago. With several 35mm and 120mm film cameras, I have begun to curate a body of work documenting the people, places, moments, and experiences I value. A series I call “A Documented Life.” To the right are a handful of recent images included in this series. In time, I will introduce even older photographic processes, like dry plate (silver gelatin) and wet plate (collodion) photography, into my work as I regain my knowledge and experience with film. Though time-consuming and labor-intensive, these forms of photography produce stunningly beautiful images and represent the type of photography my great-grandfather used to document his life. I’m excited to share this evolution with those who wish to follow my work. For current imagery and ongoing projects, you can find me on social media and my website (linked below). Drew Jensen Roycroft Renaissance Photographer Website - drewjensenphotography.com Instagram - DrewJensenPhoto | Roycroft Print Shop c. 1930 (Photo by Terence Riley Denz) Huber Press in the Roycroft Print Shop c. 1930 (Photo by Terence Riley Denz) Terence Denz in his yard c. 1930 Terence with my grandmother, Mary Denz c. 1927 Fountain at Roycroft Campus c. 1930 (Photo by Terence Riley Denz) Denz Family in the 1930s “Photographs hold great power. They connect the past with the present. They tell stories and teleport viewers to places they’ve never been. Photographs bring about associations unknown, speaking to each viewer individually. Photographs are magic.” - Drew Jensen Sunrise over Denver, 2023 by Drew Jensen Sunrise on the Flatirons, 2023 by Drew Jensen |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed